Saving the Royal Treasures Of Ur

The Fate of the Golden Helmet of Mes-Kalam-Dug

It is over twenty years since the National Museum of Iraq was looted during the chaotic capture of Baghdad in April 2003. Pictures of the ransacked galleries were a shock for all, and particularly to any who cherished the rich cultural history of Mesopotamia. I was reminded of the calamity when reading an Illustrated London News article, dated December 17, 1927 about the discovery of the Royal Tombs of Ur. It had the prosaic title, ‘The “Gold Wig” of Mes-Kalam-Dug: a wonderful discovery in a royal grave at Ur, rivalling the gold mask of Tutankhamen, and some 2000 years earlier.’ Not catchy, but this iconic artifact is a personal favourite. Later finds confirmed that it was a ceremonial helmet rather than a wig, that had been worn by Prince Mes-Kalam-Dug . Beautifully beaten from gold it would be a perfect object for the quest of another ‘Raiders’ movie. Its fate during the chaos of the Iraq wars was not apparent to a subsequent, cursory online search. It took longer and proved more intriguing than I suspected.

Why the interest in Ur? In the 1920s and 30s archaeology was headline news and the author of the ‘Gold Wig’ article, the soon-to-be knighted Leonard Woolley, was a big celebratory. He became famous while directing the excavation of Ur from 1922 to 1934. Urbane and likable, Wooley was the antithesis of the other famous archaeologist of the day, Howard Carter in that he sought publicity.

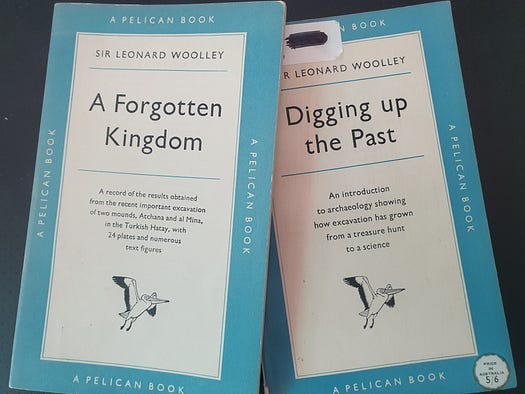

Wooley realised that funding depended on public interest generating donations. More importantly, he published throughout his life, including a series of popular books under the Pelican imprint during the 1950s which became my schoolboy introduction to Ancient History.

The excavation of Ur must be the most remarkable and most romantic archaeological expedition of all time. Playing to the Biblical connection of Ur of the Chaldees, and the birthplace of Abraham, the dig site became the most famous tourist attraction in Iraq. The visitors included Katherine Keeling, who stayed on as an illustrator, marrying Wooley in 1927 to prevent scandal.[1] Agatha Christie, the crime novelist visited shortly after, marrying Woolley’s assistant, Max Mallowan, and used the setting for ‘Murder in Mesopotamia.’ The finds from the Royal Tombs of Ur filled the newspapers. Fine goldwork, pottery, sacrificed retainers and servants and cuneiform seals that helped date and identify some of the individuals, including Mes-Kalam-Dug, ‘hero of the land.’[2] The finds brought 4th Century BCE Sumeria to life. The graphic illustrations of the grave pits are a vivid childhood memory for me, and the Helmet, of Mes-Kalum-Dug is unforgettable with its eye-catching coiffure and delicate ears.

Had it survived the destruction of the Baghdad Museum? Visiting Iraq was on my travel list before the first Iraq War, but not so now. The museum reopened in 2014 /2015, but it is hard to gauge its offerings online. I couldn’t find any mention of the royal tombs. The more I looked at the fate of the collections the more complex its story became.

I was aware that there are two copies of the Helmet. One in the British Museum, and one in the Penn Museum, Philadelphia. Both institutions had cosponsored Woolley’s dig. These are ‘electrotype’ copies, made circa 1928 under the guidance of James Ogden, a master jeweler from London and an archaeology enthusiast who donated to the dig. Ogden was a visitor to the excavation site and his offers of assistance were gratefully accepted. It was impossible to restore delicate artworks in Baghdad. There were no expert workshops, but the new Iraqi Government didn’t want the finds to leave the country. The division of discoveries was technically fifty / fifty but prize pieces like the gold helmet were excluded. Woolley agreed; the restoration would be done in London, and the helmet returned with strict deadlines. Ogden repaired the dented helmet and analysed the metal. The Golden Helmet was in fact 62.5% silver. It better classifies under the definition of electrum. Ogden’s craftsmen set about duplication by making a mold. Electrotyping is a process that lays a base film of copper on the mold and uses electrolysis to deposit the outer layer of gold. Concerned about how the colour would be changed by the copper, Ogden decided to use silver as the base, covering the additional cost himself. True enthusiast, indeed.[3]

But what of the original?

The looting of the Iraq National Museum was the worst cultural catastrophe in the modern era. The destruction of the Museum’s catalogue meant that the extent of loss is still unclear. The contemporary accounts were horrifying, claiming 170 000 items lost. More sober reports explained that that was the number of catalogued items. The number of missing items was unknown.[4] There was no way of doing a complete audit. Best estimates range from 15000 to 20000 items. In the newspaper reports there was no mention of the golden treasures of Ur.

The best account of the Museum chaos comes from Matthew Bogdanos, the Marine Colonel who was tasked to investigate the looting, arriving a few days later.[5]

Trained in Classics and Law, Bogdanos was a Homicide Prosecutor in New York and he took on the role of detective, like a modern-day Poirot, interviewing staff, neighbours, and soldiers. It was a painstaking process. Missing witnesses, conflicting accounts and misinformation all part of the mix. He identified three distinct phases of looting over three days. Some opportunistic and some highly organised targeting known collections. However, no one knew anything about the fate of the Royal Collection. It was a surprise to discover that the museum had been closed for 20 of the previous 24 years and nobody had seen the Golden artifacts since the 1990s. Rumours circulated of boxes moved to the Central Bank before the First Iraq War, resulted in the search for witnesses from the previous decade.

Bogdanos was convinced that 21 boxes were moved in 1990. Five weeks into the investigation he received permission to search the vaults of the Central Bank where he found 16. None included the material from the Royal Tombs. Another witness recalled bringing boxes to a different building. Here the vaults were under water due to destroyed pipes. Access was impossible until a National Geographic film crew provided pumps and generators. Bogdanos found five waterlogged boxes, and in his own words ‘one of the first pieces visible when the largest box was opened was the Golden Helmet of Meskalamdug.’ Thanks to National Geographic the moment was captured,[6] and there, briefly glimpsed is the beautiful, gleaming helmet. It is probably the only time I will see the original artifact. I suspect it has gone back to a different vault, but my concerns about its fate are settled.

Not so fortunate for some of the other works from the museum. A worldwide hunt for the stolen antiquities continues and includes Bogdanos who fronts an Antiquities Trafficking Unit in New York, long a centre of the illegal trade.

The Helmet of Mes-Kalam-Dug is a beautiful artifact and a symbol of our shared cultural heritage. Knowing it has survived one of the most destructive events of the recent past is comforting. It offers hope that the Golden Helmet will continue to capture the imagination of future generations, inspiring awe and wonder about all things Sumerian, a founder civilisation that still influences today.

References

[1] Winstone HVF ‘Wooley of Ur’ Martin Secker 1990

[2] Cuneiform epigraphy is commonly contested. Another interpretation is ‘Pleasing to the People’- see Marchesi G ‘Who was Buried in the Royal Tombs of Ur’ Orientalia vol 73 p 153

[3] Millerman A, ‘Interpreting the Royal Cemetery of Ur Metalwork: a Contemporary Perspective from the Archives of James R Ogden’ Iraq, vol 70 2008 p1–12

[4] Rockfell L, ‘The Rape of Mesopotamia’ Uni Chicago Press 2009

[5] Bogdanos M, ‘The Truth About the Iraq Museum’ Am J of Archaeology v109 2005 p477

[6] The Lost Treasures of Iraq,

Fascinating! Thanks Simon for yet another very interesting post.